Why the Overprints?

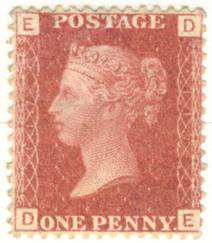

As a child I collected any stamps I could get my hands on but, as many people do, stopped collecting in my early teens. Years later, while I was laid up in bed for a month, bored half to death and recovering from an accident, I remembered this small kids collection tucked away in a box that had followed me from house to house and, pulling it out, was immediately attracted to the stamps of my homeland (England) that had been painstakingly hinged into this tattered old album. Once I was able to get out and about I looked in the telephone book and located a stamp store not far from my home whereupon I headed over there and met the owners who set about giving me a refresher course in stamp collecting.

Armed with a Scott catalog and supplies along with two brand new albums, one for Great Britain and one to contain all the other stamps I had collected, I headed home to the beginnings of what came to be an enduring passion. Within a month my childhood stamps were resting safely in their new album and I was assiduously filling in all those empty spaces in my new Great Britain album.

After a few years, I realized that I was never going to be able to afford to fill in all those lonely (and expensive) spaces at the beginning of the album but that there were many areas at the back of the book that could, with time and searching, be satisfactorily filled (and on my budget). Tucked away in this area, was the “British Offices Abroad” and, taking up less than one quarter of a page in my Scott catalog and consisting of only 27 items was an innocuous looking listing called simply “China”. Little did I know at the time that these 27 stamps (and their friends) were going to grow into something that expanded into hundreds (umm, alright, over a thousand) of pages and an obsession that continues to this day.

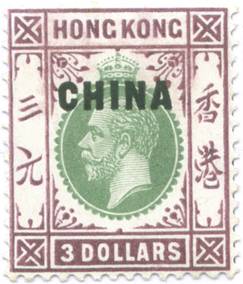

There were only two issues listed - one on the regular watermarked MCA paper which was introduced on January 1, 1917 and a second, introduced in 1922 on the watermarked script MCA paper. “Surely” I though “these cant be too difficult to obtain” and over the next year or so I managed to acquire all of these stamps except for one, the $3.

I had attended a number of stamp shows and one afternoon one of the dealers with whom I was chatting pulled out a $3 stamp which I immediately snapped up and breathed a sigh of relief knowing that finally at least one part of my stamp album was going to be complete. At the same time there was a strange sense of loss. It was over. It was finished and done. I had the entire two sets and now I would have to think about some other area of my album to fill in. There was a curious sense of disappointment as the hunt for these stamps had taken quite a while and now I would have to find something different.

As I was walking away from the table, however, this voice called me back. “Excuse me”, he said. “You’re interested in the British Offices in China are you?”. “Yes” I replied, feeling rather good at having them all. “Well, presumably you have this then?” he asked.

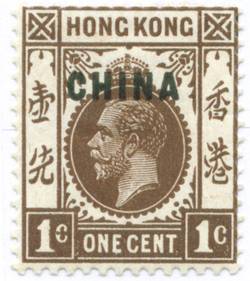

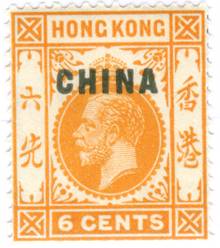

There, laying on the table in front of me, was a stamp I knew well. A simple stamp. One of the first that I ever obtained in fact. This stamp, however, was slightly different. “You have a copy of the Broken Crown then?” he asked. “Broken Crown?” I replied. “Yes”, he said. “The Broken Crown. It is listed in Gibbons.” “Gibbons?” I queried. “Scott only lists the basics” he responded. “Gibbons is the British catalog, they list many of the varieties. Look…” He pulled out a catalog I had never seen and there, listed after Hong Kong and not Great Britain, was the same listing. “China”. 27 stamps. The listing, however, looked longer. Not only were my stamps there but listed below some of the numbers were letters. Number 1 was the 1 cent brown I knew well but listed below it were more. “1a. Black Brown.” “1b Crown broken at right” “1c Watermarked sideways” and “1w Watermark inverted”. I didn’t have all the stamps I realized. I didn’t have nearly all of the stamps. “No I don’t have this” I told him. “I didn’t know that there were all of these varieties”.

“You know”, he mused, “if you are really interested in this area, you should contact the APS. I am sure that they have lots of catalogs and information on these stamps”. “I will”, I promised and, armed with both the elusive $3 stamp and this exciting new addition to my collection, I headed out.

Once I got home, and for the first time ever, I called the APS and explained that I was interested in the British Offices in China, the Hong Kong ‘China’ overprints and that I was looking for more information. “What are you using?” asked this nice lady named Gini. “Webb?”. “No”, I responded “I am using the Scott catalog”. “Ahh” she replied. “You need to get a copy of Webb. He wrote the definitive book on Hong Kong. You should also look at Perrin”. “Webb?” I thought. “Perrin?” Who were these people? “I will send you them both” said Gini. “Call me if you have any questions.”

About a week later a large and heavy package arrived addressed to me. Inside were two books. The first was a large, imposing tome filled with page upon page of dense information and the second was a thin book of only 44 pages with the cheery title “The Hong Kong ‘China’ Overprints” by K.L. Perrin.

“Hooray”, I thought. “Here is some information. Now I can learn more about these stamps.”

I started to read. I learned the story behind the stamps I had been collecting. I learned the history of the area and the reason that the stamps came into existence. Most importantly, I learned how little I really knew. There were not 27 stamps. There were 54! Not only were there 54 but these were just the basic colors of the stamps. There were dozens more varieties. There was a “Broken Crown”. There was a “Broken Kong”. The list went on. There were stamps not only overprinted ‘China’ but ‘Specimen’ as well. Not only were there stamps. There was stationary overprinted ‘China’. There were postal cards and a newswrapper. Then there was how the stamps were used from each of the different ports and the different types of cancels used upon them.

I had stumbled into something much more that I had anticipated. There was a whole world out there about which I knew nothing. This was much more than filling spaces in an album. This was something huge. Something that could occupy me for a long time to come.

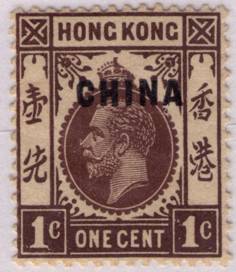

I pulled out my album and carefully mounted the two stamps. All the spaces were now filled and, in addition, I had something extra on the page. A new stamp. One that didn’t originally have its own space. One that wasn’t even in my catalog. This felt good.

I looked closer at the 26 stamps I had previously obtained. They looked different now. There was more to find, more to add. I looked closer. Something looked different about the 6 cent orange stamp. There was something I hadn’t noticed before. The lower left Chinese character on this stamp had a bar connecting the two legs. The other stamps didn’t have this. What could it mean?

I pulled out the catalog and the books I had been sent. They didn’t show this. The picture was different. Why was it different? What could this mean?

I got on the phone and called Gini. “It’s an unlisted variety” she told me. “Unlisted?” I asked. “You mean these books don’t list everything?”. “No” she replied. “People make new discoveries every day”.

I felt like I had been walking down a city street and, turning the corner, had not been greeted by another row of houses but an endless landscape stretching before me. The boundaries had changed. The catalog was not the be all and end all of my collecting. The catalog was just the beginning. Not only were there books on the stamps I loved but even they were not complete. There was so much to discover and learn. I had, unwittingly, stumbled on something that changed how I looked at stamps forever. I had stopped being a stamp collector. I had started becoming a philatelist.